Insight

Preseason Unfriendly: Lifting the lid on the Premier League’s overseas emissions

Insight

Preseason Unfriendly: Lifting the lid on the Premier League’s overseas emissions

There’s been a lot of talk of late about the English Premier League and its carbon emissions, with clubs coming under fire for travelling by air within the UK. As an example, back in January, the Nottingham Forest squad took a 20-minute flight from East Midlands Airport to Lancashire to fulfil an FA Cup fixture with Blackpool – a journey of 135 miles. More recently, research by the BBC found that 81 out of 100 English domestic matches between 19th January and 19th March this year involved short-haul flights.

However, our own research reveals that the emissions impact of domestic air travel is a drop in the ocean compared to another area of club transport: overseas preseason tours.

It wasn’t all that long ago that Premier League clubs would play local teams from lower divisions over the summer months as part of their preparations for a new season. Such localism has since been replaced by international expansionism, as clubs seek to capitalise on lucrative overseas markets, especially in the US and South-East Asia. The Athletic has even reported that the Premier League has held formal discussions over hosting a “39th game” of a regular league campaign abroad, as seen in the now-annual NFL games held in the UK and Germany, with the Camp Nou in Barcelona reportedly in line for a slice of the action.

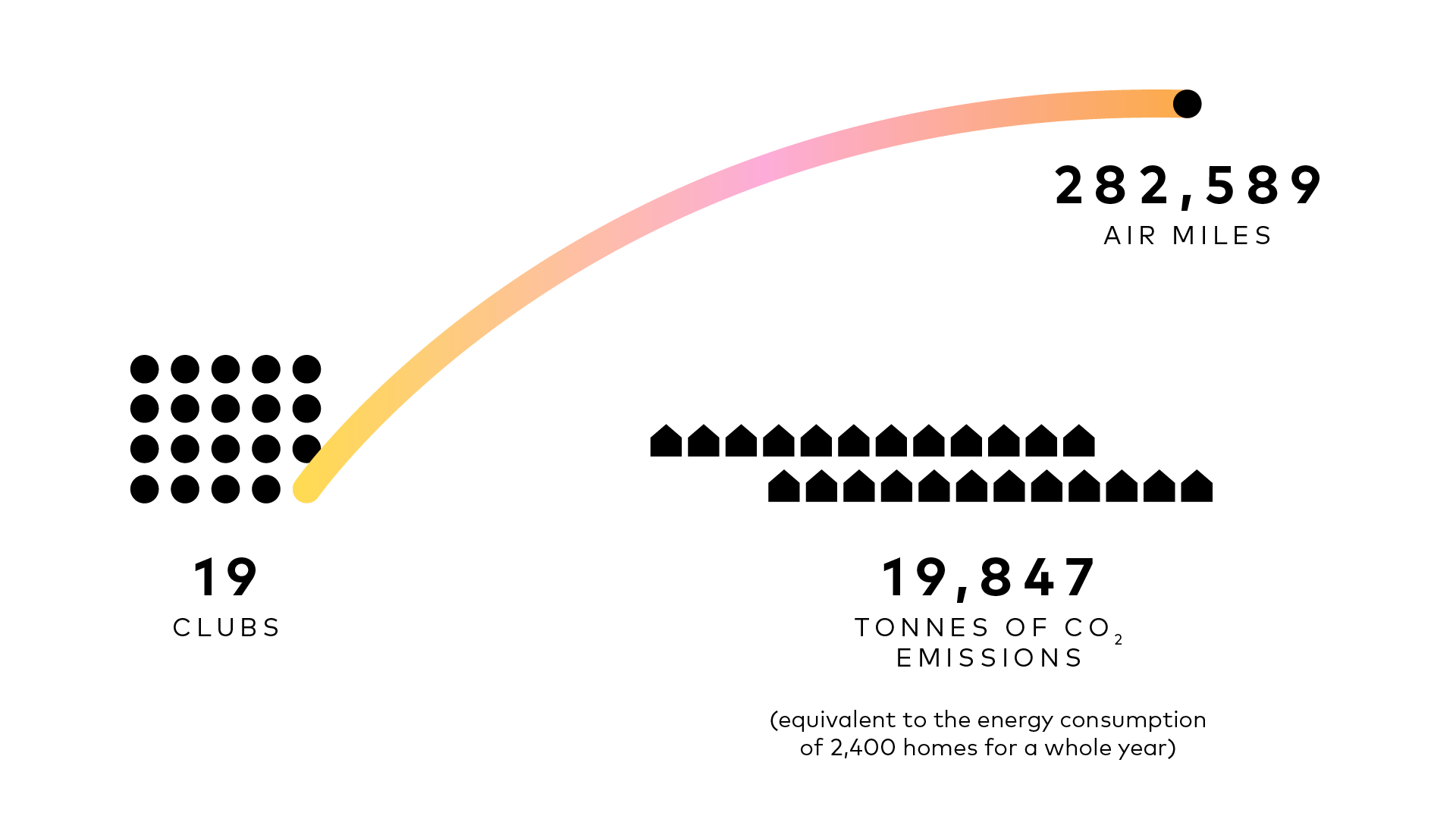

But what about the carbon costs of these (for now) meaningless friendlies that have become so commonplace? We looked at the data from the 2022/23 pre-season, when 19 out of the 20 Premier League clubs jetted off for pre-season tours, to find out more.

Can overseas friendlies ever be justified given the carbon cost?

The results of our data analysis were mind-blowing.

19 clubs.

282,589 air miles.

19,847 tonnes of CO2 emissions.

(equivalent to the energy consumption of 2,400 homes for a whole year)

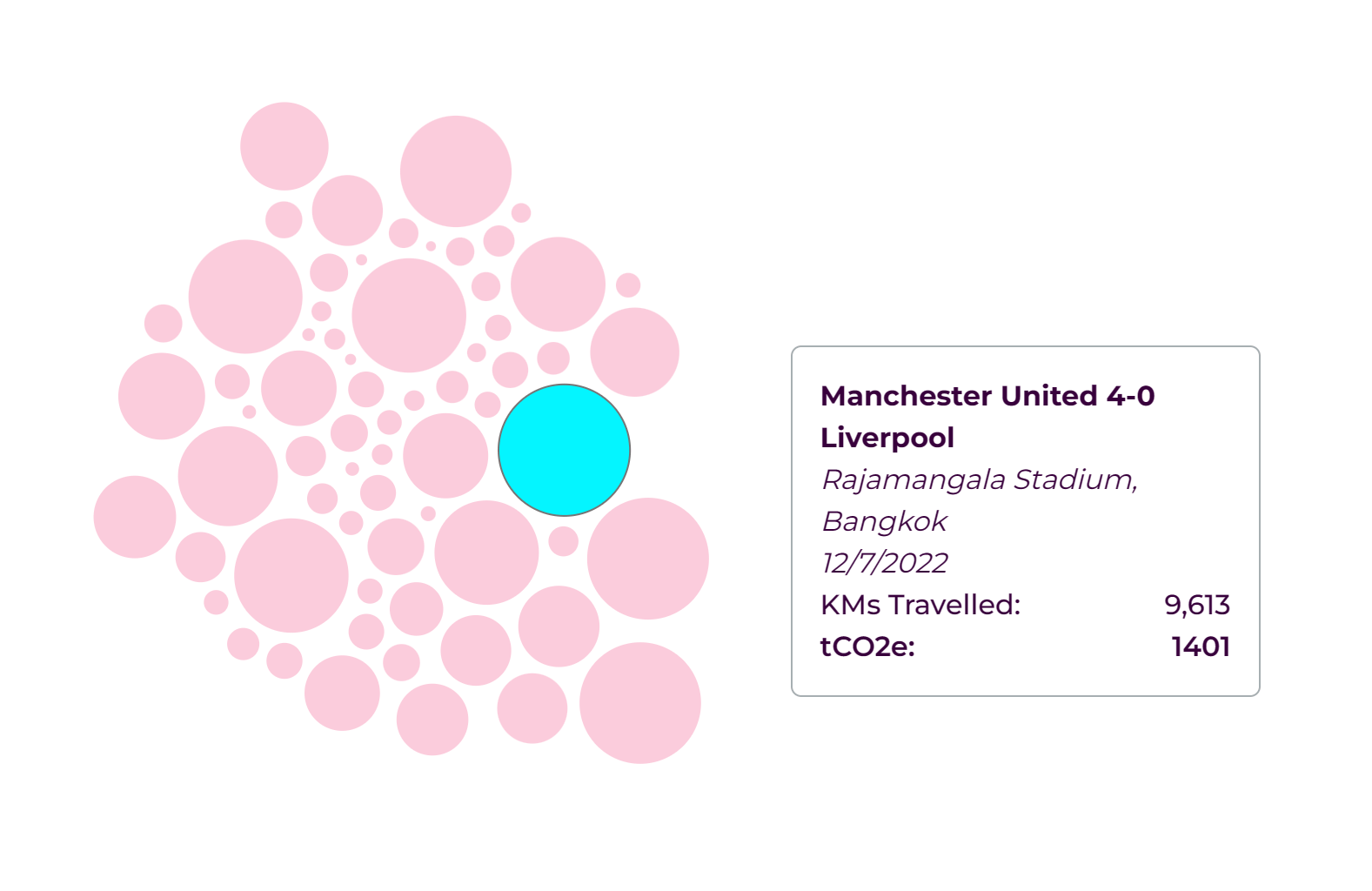

On 12th July 2022, Manchester United beat Liverpool 4-0 at the Z stadium in Bangkok, Thailand. The two teams’ transport emissions totalled an estimated 1,400 tonnes of CO2. That’s 7,000 times as much carbon emissions compared to when the two teams play each other domestically (Liverpool to Old Trafford via coach = 0.2 tonnes of CO2).

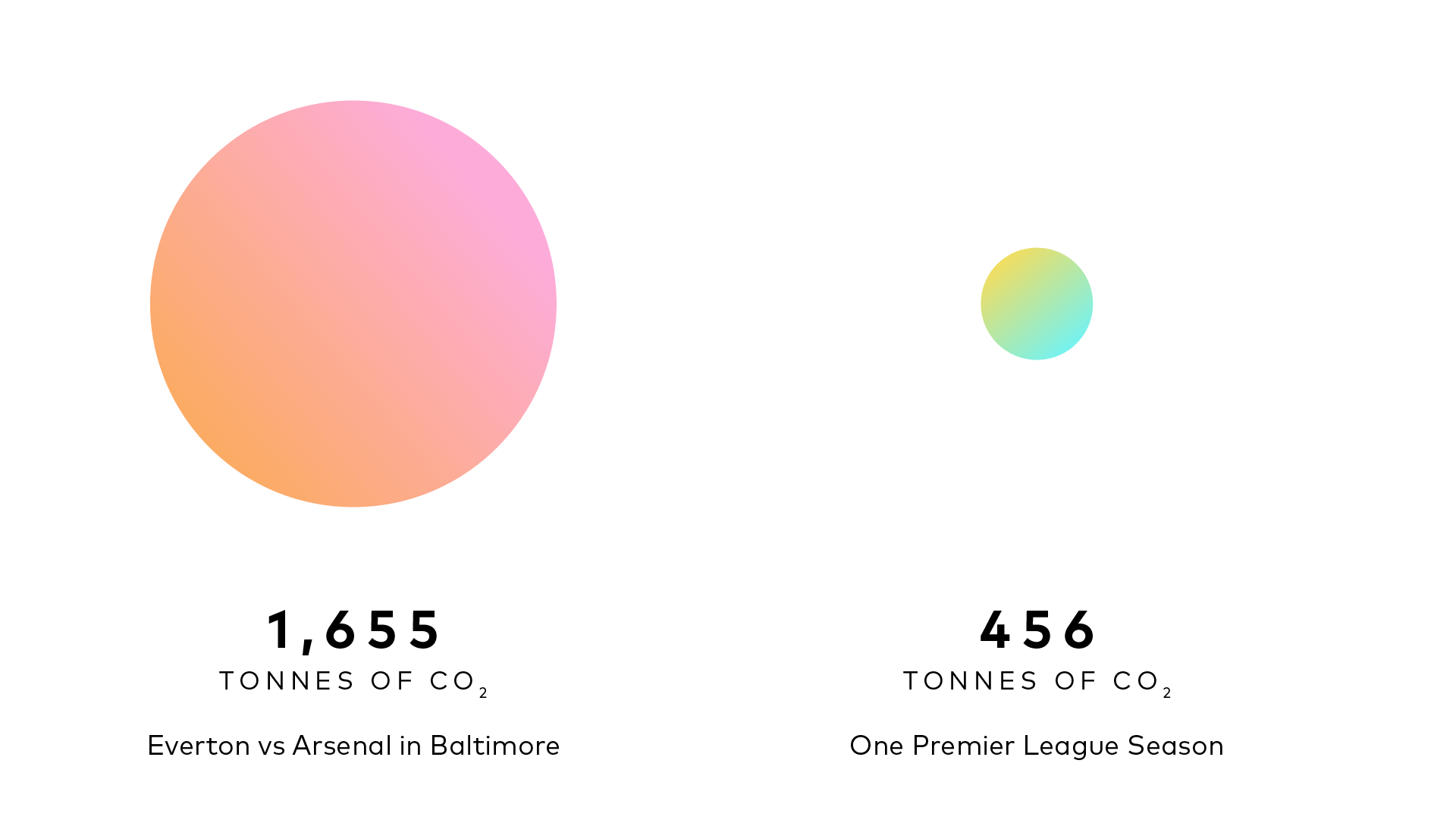

And the prospect of two Premier League teams playing each other abroad is by no means an anomaly. In the same pre-season, Arsenal played FC Nuremberg in Germany before flying out to Baltimore in the US to play Everton. So that’s 880 tonnes of CO2 for Arsenal’s return flights, plus a further 775 tonnes for Everton’s own transport emissions, giving a grand total of 1,655 tonnes of CO2.

*We’ve assumed that any journey over 150 km was taken as a domestic flight

Yes, this one overseas friendly equates to 3.62 entire domestic Premier League seasons of carbon emissions (or 1,379 matches combined). And that doesn’t factor in the emissions from the fans following their teams across the globe.

This year, the Premier League has already announced that six of its clubs – Aston Villa, Brighton, Brentford, Chelsea, Fulham and Newcastle United – will play nine matches against each other in five different US cities. West Ham and Tottenham will play each other in Perth, Australia – over 9,000 miles from home.

The Premier League and its clubs have signalled their intentions around sustainability through various statements and strategies, but it’s difficult to square such documents with the realities of pre-season friendlies abroad.

How can the Premier League reduce its transport emissions?

As our data shows, there is a clear case for near-term behaviour change by the Premier League.

In an ideal world, all 20 Premier League clubs would commit to playing all their pre-season friendlies in the UK and against domestic teams.

If that is too much to ask, the clubs could consider limiting their overseas travel to Europe (as with the Champions League and other pan-European competitions). Long-haul travel entails significantly more carbon emissions, with even less of a sporting excuse. Returning to our Arsenal vs Everton example, Arsenal’s return flight to Baltimore produced eight times the CO2 emissions as their travel to Nuremberg (880 tonnes vs 110 tonnes).

But what about the fans, you say? Don’t overseas fans deserve the chance to see their Premier League heroes in action? From a sustainability perspective, the ends simply do not justify the means. If the league was really serious about giving access to more fans in more parts of the world, perhaps a better idea would be to set up dedicated fan parks overseas.

But what about the profit motives, you say? Yes, overseas pre-season friendlies drive ticket and shirt sales in emerging markets. But the reality these days is that the vast majority of Premier League clubs’ revenues come from TV broadcasting rights, so isn’t it enough that fans can watch the games that actually matter wherever they are in the world?

The numbers are stark, but change is very possible. As ever with sustainability, the data tells us a story – one that we can’t afford to ignore.

See the full data story at PreseasonUnfriendly.com

Do you have an idea for a data experiment you want to collaborate on? Check out FutureFridays!