Insight

Airi Ryu on inequality in the coffee value chain

Insight

Airi Ryu on inequality in the coffee value chain

Coffee producers from the Global South do not reap profits as high as importing countries from the Global North, contributing to economic inequality among producing countries. Sustainability data expert Airi Ryu walks us through the history of the coffee industry and how consumers can make more informed purchases to create positive change.

My Own Journey in Coffee

My oldest memory of coffee is the cappuccino my parents would buy when we were on holiday. For my 7-year-old self, a cappuccino was this European drink that we didn’t have in Japan. It smelled super good, but I was too young to have any. I remember my favourite part was the cinnamon stick that came with the cappuccino. I wasn’t allowed to drink it, but my mom always let me mix the foamy milk with the cinnamon stick. I don’t know why, but I loved doing it so much that it eventually became a bit of a ritual — whenever my parents got a cappuccino, I got to be the one to stir it.

Looking back, I think what attracted me to coffee was always the culture. The flavour itself was definitely an acquired taste for me, but the awe I felt every time I entered a quaint little cafe was unforgettable. It made me feel like the world was borderless, and that I could touch parts of Earth I had never been to. That somehow I was connected to the other side of the planet through a shared love of coffee.

But it wasn’t until I got much older that I started paying attention to where my coffee actually came from. For some reason, I had never taken the time to think, let alone learn, about the origins of coffee. I suppose this is common for many of us who only buy food and drink from neatly stocked shelves. Our purchasing process is so detached from the realities of agriculture, it’s almost as if our food system doesn’t want us to know how it arrived to us.

So as part of my journey to better understand the coffee system, I’ve tried to immerse myself in lots of different parts of the system. I started as a barista and then expanded into doing market research by interviewing people ranging from coffee company CEOs to coffee producers. More recently, I’ve visited coffee farms in Kenya and Vietnam to hear and experience the realities of a coffee farmer.

The following insights share an accumulation of my knowledge built up from trying to have the most possible holistic view of the coffee system.

The Coffee Value Chain’s North-South Relationship

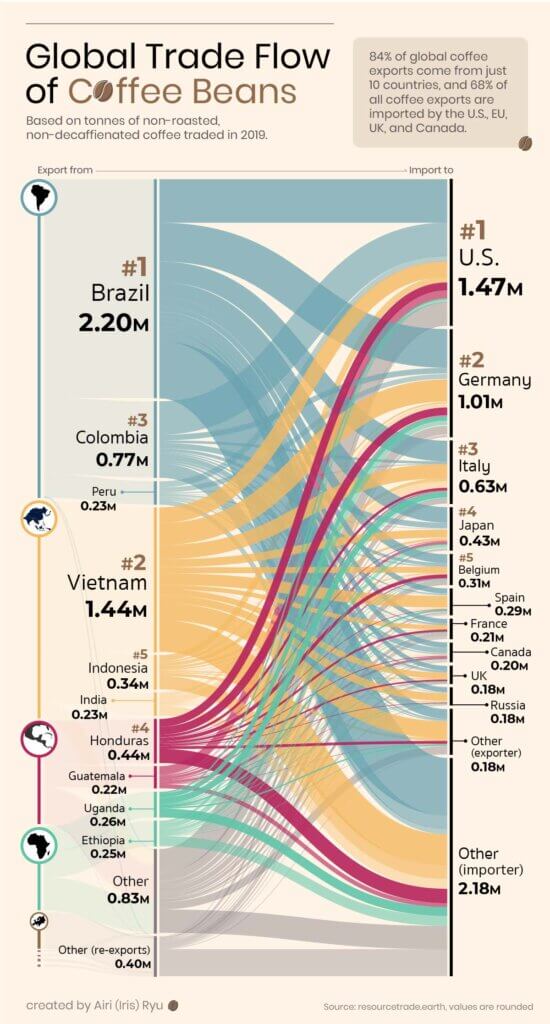

This sankey diagram I made highlights how dependent importing countries are on a small number of countries to provide their coffee beans.

The coffee value chain has a so-called vertical supply chain, otherwise known as a “North-South” relationship, where production and consumption are largely divided between the Global South and the Global North, respectively (1). Almost all coffee is grown in an area called the “Coffee Belt”, which spans countries in Latin America, Africa and Asia that are on and around the equator.

Within the Coffee Belt, 84% of global coffee exports come from just 10 countries, of which almost 58% comes from just Brazil, Vietnam and Colombia. In direct comparison, around 74% of all exported coffee is imported by the US, the EU, the UK, Japan and Canada.

The North-South relationship in and of itself is not an issue. It is when this relationship is also a “win-lose” relationship, where the Global North takes a disproportionate share of the industry value, that it becomes problematic. This is unfortunately the case for coffee.

It is estimated that only 10% of the industry value remains in coffee-producing countries, creating a wealth drain out of countries that are already poor (2). Data from the last 30 years also show that coffee growers on average consistently receive just 99 US cents/lb of green coffee, which amounts to only 5-18% of the global retail price at which coffee beans are sold in the Global North (3). In London, where I live, a double espresso typically costs me around £2.80 ($3.60). A double shot will have around 20 g (0.04 lb) of ground coffee, meaning you can receive around £56 ($71) per pound of green coffee. Compare that to the $0.99 the farmer gets, and it’s not too difficult to understand how coffee-consuming countries keep 90% of the industry value.

Coffee’s Colonial Legacy

Several reasons could explain this wealth drain. The first is coffee’s inherent colonial legacy.

In the 1700s, when coffee culture was rapidly growing in Europe, the Dutch East India Company and the French East India Company began to use their colonial power to secure regular shipments of coffee to the Netherlands and France. Plantations were introduced into many colonies by clearing native forests and replacing them with large plantations where coffee was cultivated using slave labour. Green coffee produced on these plantations was to be given solely to the conquerors, and local communities had no access to it. Soon after, the British East India Company followed suit, destroying native forests and wildlife to secure their own share (4).

Much of this colonial history has left a big stain on modern coffee culture. The current coffee value chain and how coffee beans are traded remains largely unchanged since the colonial days: The majority of coffee is exported for economic gains in the Global North, and the local community derives little benefit. In 2019, the top 12 exporting countries (representing 90% of the world’s coffee exports) consumed less than 26% of the coffee they produced (3). Many coffee-producing countries don’t have a well-established coffee culture, largely due to their long history of not having access to the coffee that they themselves have grown.

Since the colonial days, coffee has always been imported and exported before it gets roasted — this is what is known as green coffee. However, one of the most lucrative stages of the coffee value chain is at the roasting stage, as proven by how little farmers get paid for their coffee in comparison to the retail price. For example, during my time in Vietnam working on a coffee farm, my farmer friend told me that if he sells his coffee roasted, he can sell it for more than 3 times the price of his green coffee!

Photo of Manh Duong, my farmer friend who takes care of his organic coffee farm in the Dak Lak region of Vietnam.

As a society, we tend not to challenge or question systems that have been around for a long time. Coffee is no different. But what if we didn’t normalise history, and we instead imagined a new future that is full of systems change?

What if we challenged this notion that coffee needs to be shipped as green coffee, and explored the idea of shifting wealth by moving the value-add step to the producing countries?

Coffee and Climate Justice

This wealth drain is a major issue because many coffee producers don’t receive a reasonable living income in current market conditions (5). The average poverty rate in the top 12 coffee exporting countries is 25.1%, compared to just 1.7% in importing countries (6). Coffee prices are notoriously volatile, and coffee producers are facing increasing threats from global warming and extreme weather events that make the reliability of their coffee yields precarious. Smallholder coffee farmers who own less than 5 hectares of land are particularly vulnerable to shocks and stresses, but they make up 95% of the world’s coffee farms (7)(8). To safeguard their livelihoods, many of them must rely on public policies and initiatives to support them. That said, with the liberalisation of the coffee market, much of the decision-making power has now transferred to large multinational corporations headquartered in the Global North (1).

Without immediate plans to adapt to the climate crisis, by 2050, the amount of land suitable to grow Arabica coffee could decline by as much as 70-75% in some areas (9). Increased temperatures will lower crop yield and bring in new pests and diseases for which most farms are ill-prepared (10). A changing climate also affects crop quality, forcing many producers to sell coffee at a lower price (11).

Coupled with an existing coffee system that already disbenefits farming communities, the climate crisis exacerbates existing inequalities by making it more difficult for coffee producers to earn a stable income, while simultaneously requiring them to invest in long-term adaptation strategies with disposable income that they don’t often have.

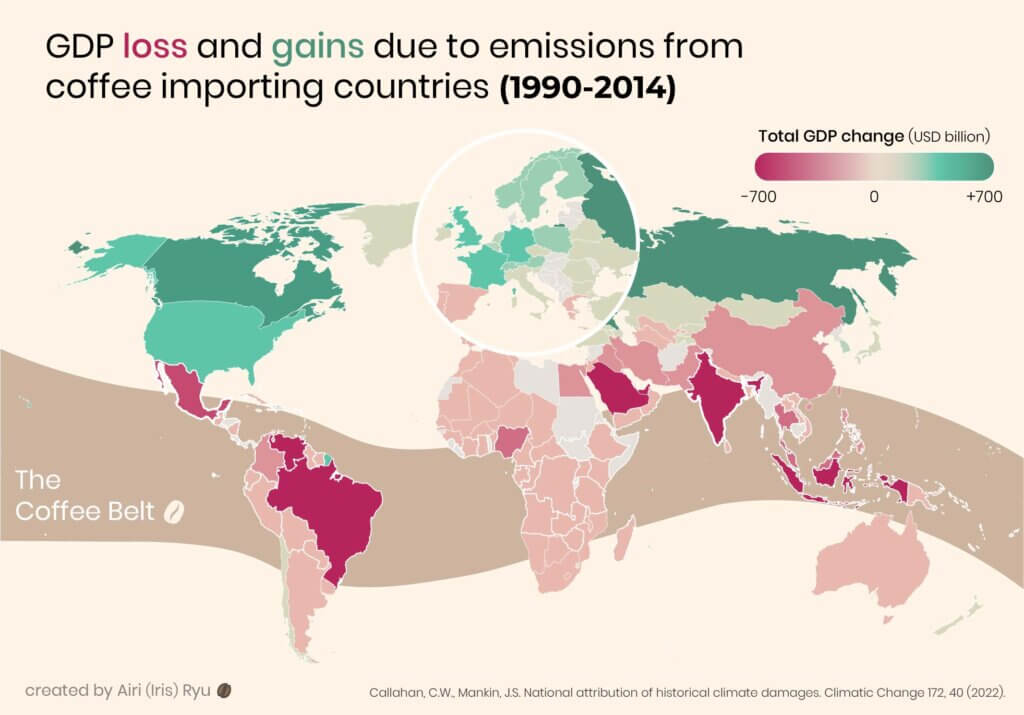

This visual highlights how, between 1990 and 2014, Coffee Belt countries incurred a disproportionate loss in GDP due to GHG emissions by the top 12 coffee-importing countries.

To add fuel to the fire, coffee-producing countries contribute little to the climate crisis. The average per capita GHG emissions of the top 12 exporting countries in 2021 was less than half of the importing country average of 10.9 tCO2e/capita (12). The visualisation above shows how much GDP gain or loss a country has experienced between 1990 and 2014 as a consequence of greenhouse gases emitted by the top 12 coffee importing countries. As the visual makes clear, almost all the countries in the Global South, including those on the Coffee Belt, have experienced a loss in GDP as a consequence of importing countries emitting greenhouse gases.

In other words, the countries that are the least responsible for the climate crisis are paying for the consequences, while high-emitting countries wreak economic benefits at the cost of the Global South. It is therefore imperative that countries with more wealth and climate responsibility help those with less.

At present, not enough climate finance is moving from the Global North to the Global South. In 2021, the top 12 coffee-exporting countries received approximately $20 billion in public funding from the Global North for climate mitigation and adaptation initiatives, which equates to less than 3% of the 2021 budget for the United States Department of Defense (13)(14). As of 2018, only 1.7% of the world’s climate finance targeted smallholder farmers (15), and currently only 5% of coffee farmers have the finances to build resilience into their farming practices (10). Without the finances to build climate resilience, the coffee sector will face exacerbated deforestation and possible crop extinction.

If the world wants to continue to drink coffee, the only way forward is to address the coffee price crisis and help producers earn more money so they can safeguard the future of coffee and their livelihoods.

What can we do as coffee consumers to push for change?

The issues I address above really only scratch the surface of the social and environmental complexities of the coffee value chain. It can feel daunting to know that many of these issues are systemic and built off of centuries of history. But I urge you to never stop being curious, and to continue to challenge the status quo. There is always something we can do, no matter how small.

As coffee consumers, there likely isn’t one action we can take that will create a seismic shift in the way we operate. Regardless, I would like to share some tips and actions that I feel are meaningful. That being said, I would like to caveat my recommendations based on the fact that I come from Japan and currently live in the UK. My views are from a person who lives in the Global North and experiences the coffee world as a typical consumer from importing countries, and my advice is therefore most apt for those who experience the world in a similar way.

1. Advocate for Climate Transparency

I think one of the most powerful things we can do as consumers is to demand more information from coffee shops, roasters, and importers. Information about how much farmers are getting paid, the carbon and water footprint of the coffee, the percentage of female ownership of coffee farms, and how much deforestation or reforestation is associated with the coffee being produced.

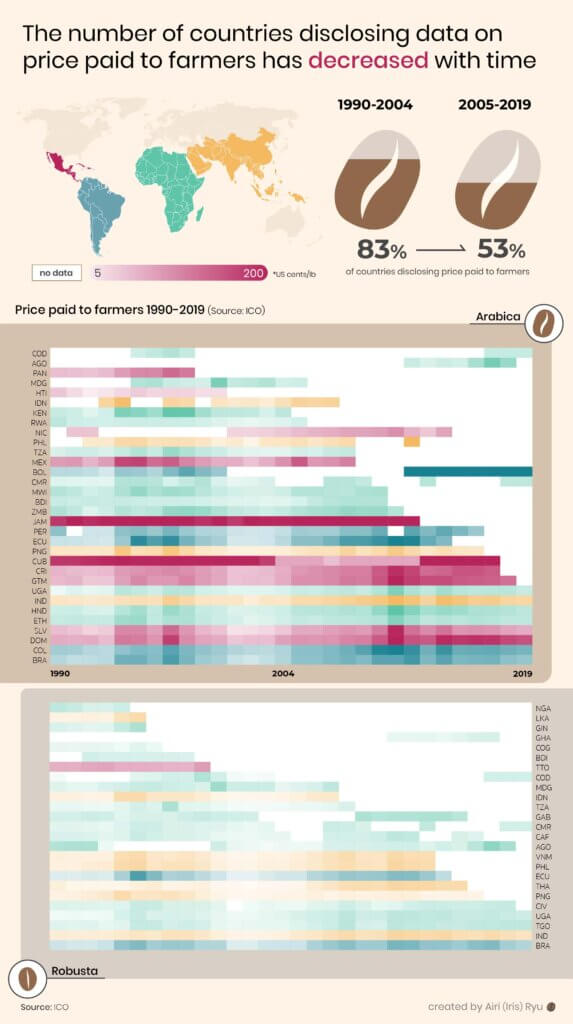

As this visual makes clear, the period 1990-2019 saw a notable decrease in data availability on price paid to farmers due to the liberalisation of the coffee market. Additionally, farmers tend to receive less from selling Robusta coffee than Arabica.

For example, the International Coffee Organisation (ICO) discloses data on the price paid to coffee farmers, along with the average retail price in importing countries. This is valuable because we can see how much or little coffee farmers are getting paid. This information allows us to hold the coffee industry accountable for unjust decision-making, and thereby pressures the industry to do better.

However, due to the liberalisation of the coffee market, data on the price paid to farmers has been continuously decreasing over the years, with only 26% of countries disclosing this information in 2019, compared to 78% in 1990 (3). Power has moved from governments to private corporations, which have become increasingly opaque around what they do at origin. There is, therefore, an opportunity for us as consumers to pressurise these companies to disclose this information by sending emails requesting this data, or asking store managers for details on their operations at origin.

2. Buy Products Closer to Producing Countries

One of the best solutions to address the wealth drain in the coffee value chain is to bring more attention to the coffee-producing countries.

Throughout my journey to learn more about coffee, I have encountered beautiful humans radically trying to reimagine the existing coffee culture. Specialty coffee shops that roast at origin and coffee producers experimenting with new fermentation methods are just a few examples. However, these types of products are not readily available in most of the world, so the best we can do is buy coffee from people who have personal relationships with people at origin.

More often than not, specialty coffee shops are closer to origin than coffee giants like Starbucks and Costa. If you have the financial cushion to, opt for specialty coffee shops if having coffee out, or buy capsules from curated coffee shops rather than giants like Nestle. Even better if you can find coffee shops that give you information about the farmer and their relationship with them!

3. When Travelling, Choose Local

Soul Roastery, a specialty coffee shop in Dak Lak, the Robusta “coffee central” of Vietnam.

If we can boost coffee culture in producing countries, we can create more demand for domestic coffee consumption and South-to-South coffee trade. Coffee prices would then be less dictated by importers, and the producing countries could become more self-sufficient.

As consumers, we can support this by choosing to experience existing local coffee culture when we are travelling to coffee-producing countries. So opt out of going to global coffee chains when abroad, and instead choose the places locals go to. When you return from your trip, share your experiences with friends so they can live vicariously through you 🙂 (or do the same when they travel overseas).

4. Continue to Educate Yourself

One of the most beautiful things I realised through this journey of mine is how much I have learned about the world through coffee. In the beginning, coffee was just a fancy European drink that we didn’t have in Japan. But now I know it isn’t just a fancy drink. There is a whole army of people working really hard to deliver me this one beverage, and each cup is different. The sweet Vietnamese coffee is distinctly different from the smooth Costa Rican chorreador, which tastes like tea when compared to the Italian espresso. Some people who work in the space do it for the love of coffee, and some do it out of necessity. Some see it as their way of decolonising their country, and others see it as a way to play their part in solving the climate crisis. Everyone has a different answer to what coffee means to them and it has been incredibly inspiring to hear people’s stories.

For me, I want my approach to coffee to reflect my life values and how I want to exist on this planet. If I am consuming something, I want to make informed decisions, rather than easy decisions. I want to give people a platform (which they often don’t have) to voice their thoughts and lived experiences to the world. I want to give credit where it’s due.

I truly believe in the power of ripples turning into tides, and I hope that some of the data-backed tips and insights shared above can help create a little ripple in the water of social justice. Hopefully the next time you drink a cup of coffee, you’ll be reminded that behind that sip is an entire world of people working hard, and that there is much work to be done to support them.

References

- Ahmed, S., Brinkley, S., Smith, E., Sela, A., Theisen, M., Thibodeau, C., Warne, T., Anderson, E., Van Dusen, N., Giuliano, P., Ionescu, K.E., Cash, S.B., 2021. Climate Change and Coffee Quality: Systematic Review on the Effects of Environmental and Management Variation on Secondary Metabolites and Sensory Attributes of Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora. Frontiers in Plant Science 12, 2120. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.708013

- Chiriac, D., Naran, B., Falconer, A., 2020. Examining the Climate Finance Gap for Small-Scale Agriculture. Climate Policy Initiative Supported by IFAD.

- Dodman, D., Karapinar, B., Meza, F., Rivera-Ferre, M.G., Sarr, A.T., Vincent, K., 2014. IPCC WFII AR5 Chapter 9: Rural Areas. IPCC.

- Global Coffee Platform, 2023. Living Income in Brazilian Coffee Production.

- Global Coffee Platform, 2022. Sustainable Coffee Purchases Snapshot 2021.

- ICO, 2020. International Coffee Organization – Historical Data on the Global Coffee Trade [WWW Document]. URL https://www.ico.org/new_historical.asp (accessed 11.4.21).

- International Trade Centre, 2021. The Coffee Guide (No. Fourth edition). ITC, Geneva.

- Jones, M.W., Peters, G.P., Gasser, T., Andrew, R.M., Schwingshackl, C., Gütschow, J., Houghton, R.A., Friedlingstein, P., Pongratz, J., Le Quéré, C., 2023. National contributions to climate change due to historical emissions of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7636699

- Miatton, F., Amado, L., 2020. Fairness, Transparency and Traceability in the Coffee Value Chain through Blockchain Innovation. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICTE-V50708.2020.9113785

- Morris, J., 2019. Coffee A Global History, Edible. Reaktion Books Ltd, London, UK.

- OECD, 2022. Climate Change: OECD DAC External Development Finance Statistics – OECD [WWW Document]. URL https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-topics/climate-change.htm (accessed 8.18.23).

- Solymosi, K., Techel, G., 2019. Brewing up climate resilience in the coffee sector: Adaptation strategies for farmers, plantations, and producers.

- The World Bank, 2023. Multidimensional Poverty Measure [WWW Document]. World Bank. URL https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/brief/multidimensional-poverty-measure (accessed 8.18.23).

- U.S. Department of Defense, n.d. DOD Releases Fiscal Year 2021 Budget Proposal [WWW Document]. URL https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/2079489/dod-releases-fiscal-year-2021-budget-proposal/https%3A%2F%2Fwww.defense.gov%2FNews%2FReleases%2FRelease%2FArticle%2F2079489%2Fdod-releases-fiscal-year-2021-budget-proposal%2F (accessed 8.18.23).

- Utrilla-Catalan, R., Rodríguez-Rivero, R., Narvaez, V., Díaz-Barcos, V., Blanco, M., Galeano, J., 2022. Growing Inequality in the Coffee Global Value Chain: A Complex Network Assessment. Sustainability 14, 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020672

We want to thank Airi for sharing her enthusiasm and knowledge about this industry that touches so many of us every day. We hope her article has inspired you to think about ways to advocate for supply-chain transparency and accountability in the context of climate change, whatever the industry. At infogr8, we join the dots so you can do more with data. Send us a message to find out more.

About Airi Ryu

Airi is a sustainability expert who loves telling stories about social and ecological issues through data. Her current passion lies in the food system and exploring the effects of climate change and human behaviour on agricultural supply chains. She hopes her work can help inform more people about how what we eat and grow influences society and the Earth.