Insight

Charting pet homelessness with Mars Petcare

Insight

Charting pet homelessness with Mars Petcare

A stray dog in your street. What would you do?

You’re walking along a street in your neighbourhood and notice a dog you’ve never seen before. It’s a little scruffy, with no collar. What do you do?

I’ll be honest. I’d walk on, at least the first time I saw it. I live in a rural part of the UK, where true strays are rare. I know several dogs who often go walkies alone for a few hours, enticed by the heady scent of a rabbit or pheasant, leaving their anxious owners to shout and search. If I knew who its owners were, I’d contact them. If it looked to be suffering, I’d contact an animal charity. But if neither of those applied, I’d continue on my way, assuming the hound would soon be reunited with its human (and its collar).

Leaving the dog to its own devices would put me in a minority, a new poll reveals. If they saw a suspected stray dog, 65% of people say they’d do something, according to a large international survey by Mars Petcare. Thirty-eight percent would be kind to the animal by feeding it (30%), playing with it (16%), or both. Almost as many (37%) would take action by trying to find the owner (16%), reporting it to local authorities (12%), alerting an animal shelter (13%), or even transporting the dog there themselves (9%).

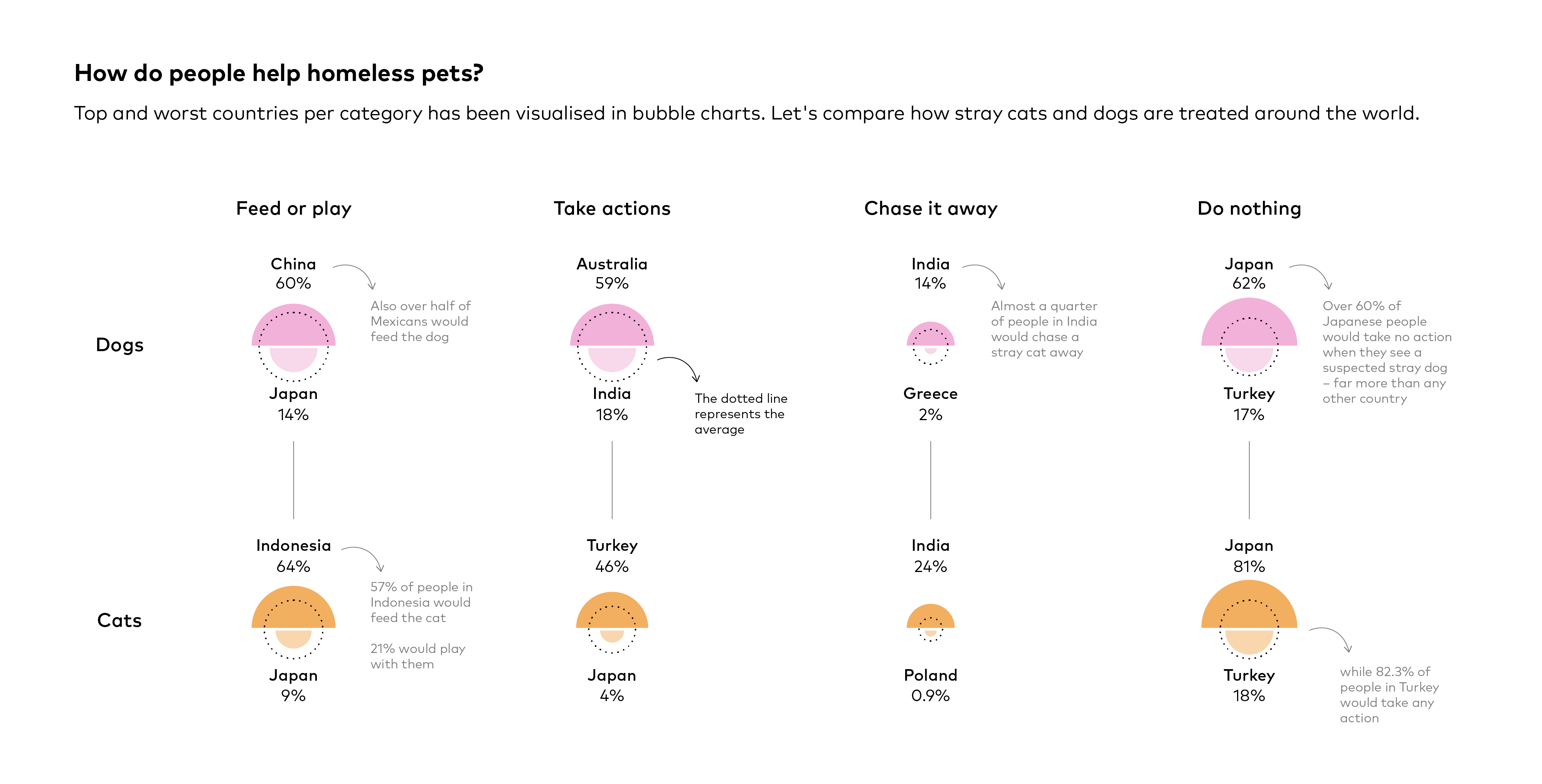

The survey of people in 19 countries, part of Mars Petcare’s State of Pet Homelessness Project, shows attitudes towards strays differ enormously across the globe. In Mexico, 51% say they would feed the dog, but this drops to 5% in Japan. In fact, 63% of Japanese people would do nothing if they spotted a suspected stray – far more than any other country. In Australia, 27% of people would try to find the dog’s owner; in Brazil and India, nobody would. Australia also has the highest share of people who say they’d take the animal to a shelter: 19%, versus 9% globally. The stats for cats are similar – and just as diverse across countries – although overall, slightly fewer people would take action to help a stray feline (25%, versus 37% for canines).

Chart 1: How do people help homeless pets?

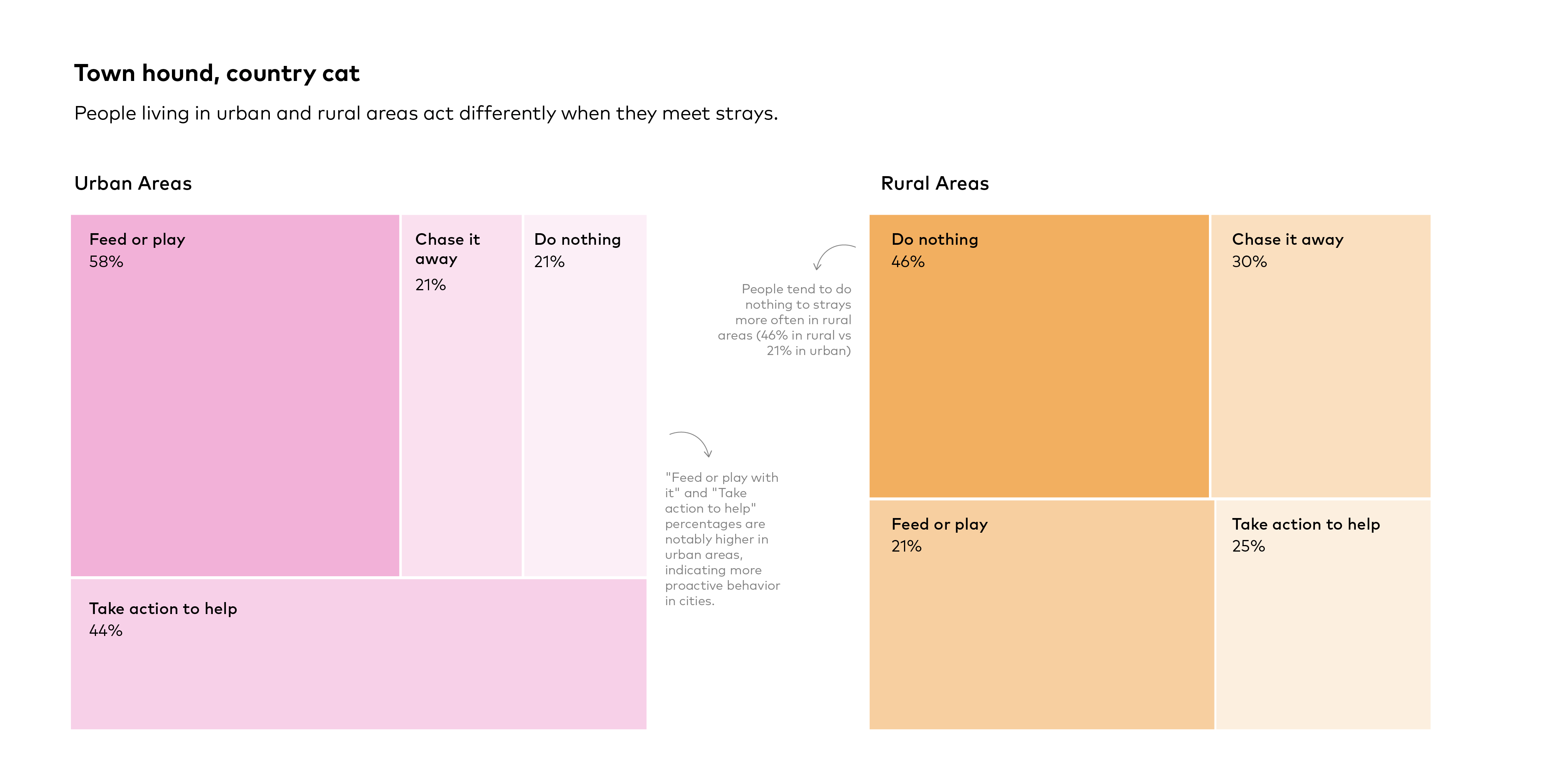

Why do people say they treat stray animals so differently, depending on where they live? Cultural factors likely play a substantial role – and may relate to the very different levels of risk strays pose to humans in different places. Across the world, 9% say that if they saw a street dog, they would chase it away. But this rises to 27% in India, where rabies is a serious problem and a single dog bite can kill. Globally, 99% of human rabies cases are caused by dog bites. Rabies is mainly a disease of the rural poor, which may explain why, in many lower-income countries surveyed, those living in rural areas are more likely than urbanites to walk past street dogs, or shoo them away. (The same attitudes apply to street cats, which can also transmit rabies and other diseases to humans.) City dwellers, meanwhile, are more likely to act kindly towards strays or take action to help them than their country-dwelling counterparts.

Chart 2: Town hound, country cat

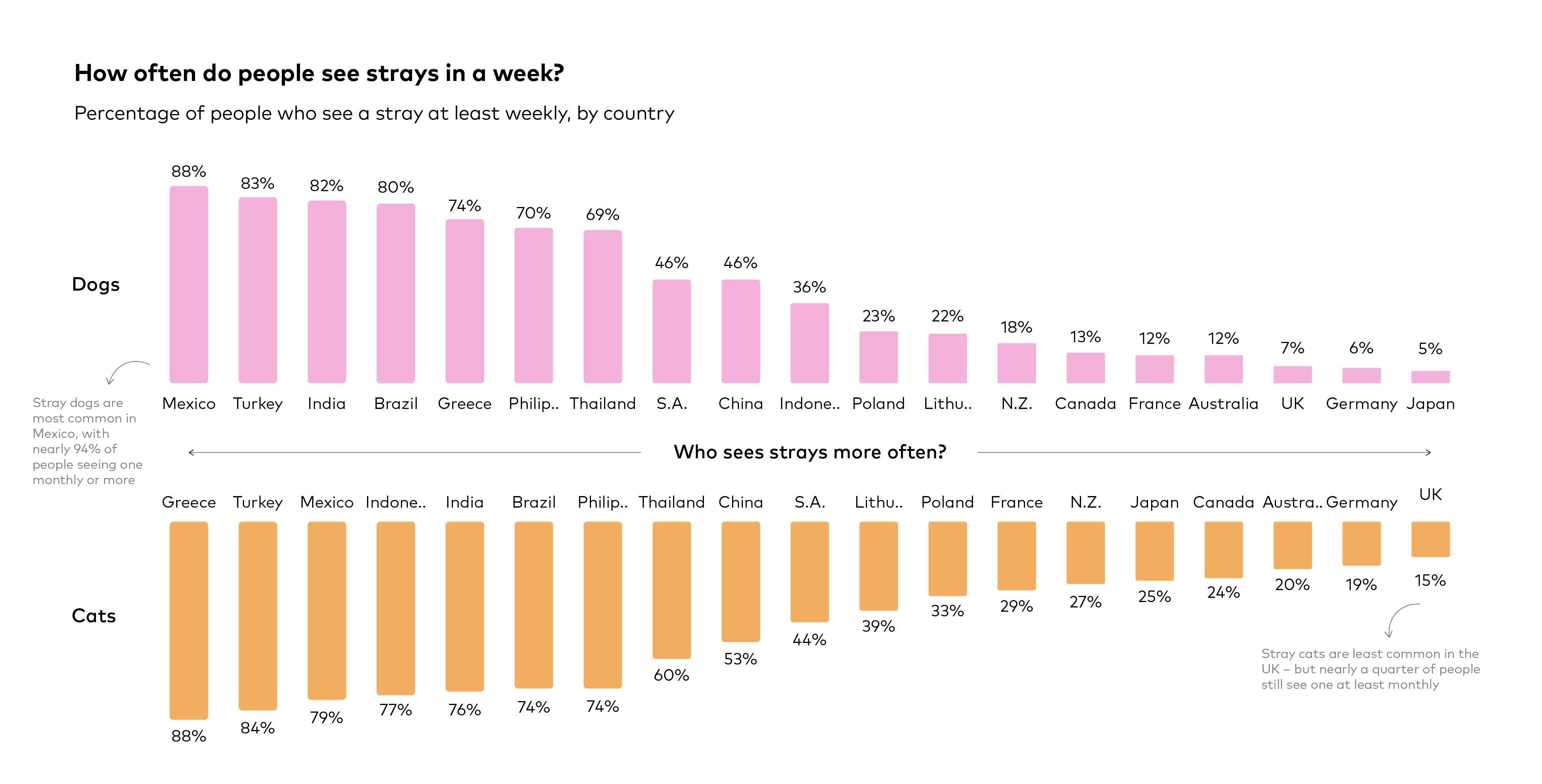

An important driver behind the diversity in attitudes seems to be that homeless animals are vastly more common in some countries than others. Two-thirds (66%) of Mexicans see street dogs every single day. But the same proportion of Japanese people have never seen one in Japan. France has just 1,000 street dogs, according to other Mars research. That’s 1,000 too many, but it’s a tiny fraction of the 52.5 million dogs living on Indian streets, with an additional eight million in shelters. China has a jaw-dropping 132 million stray cats and dogs, including those living on streets and in shelters. That’s over half of all the dogs and cats in the country – about one stray for every 11 people. Even the UK has over a million stray cats, mostly living on the streets – a statistic that surprises and shocks me.

Chart 3: How often people see strays

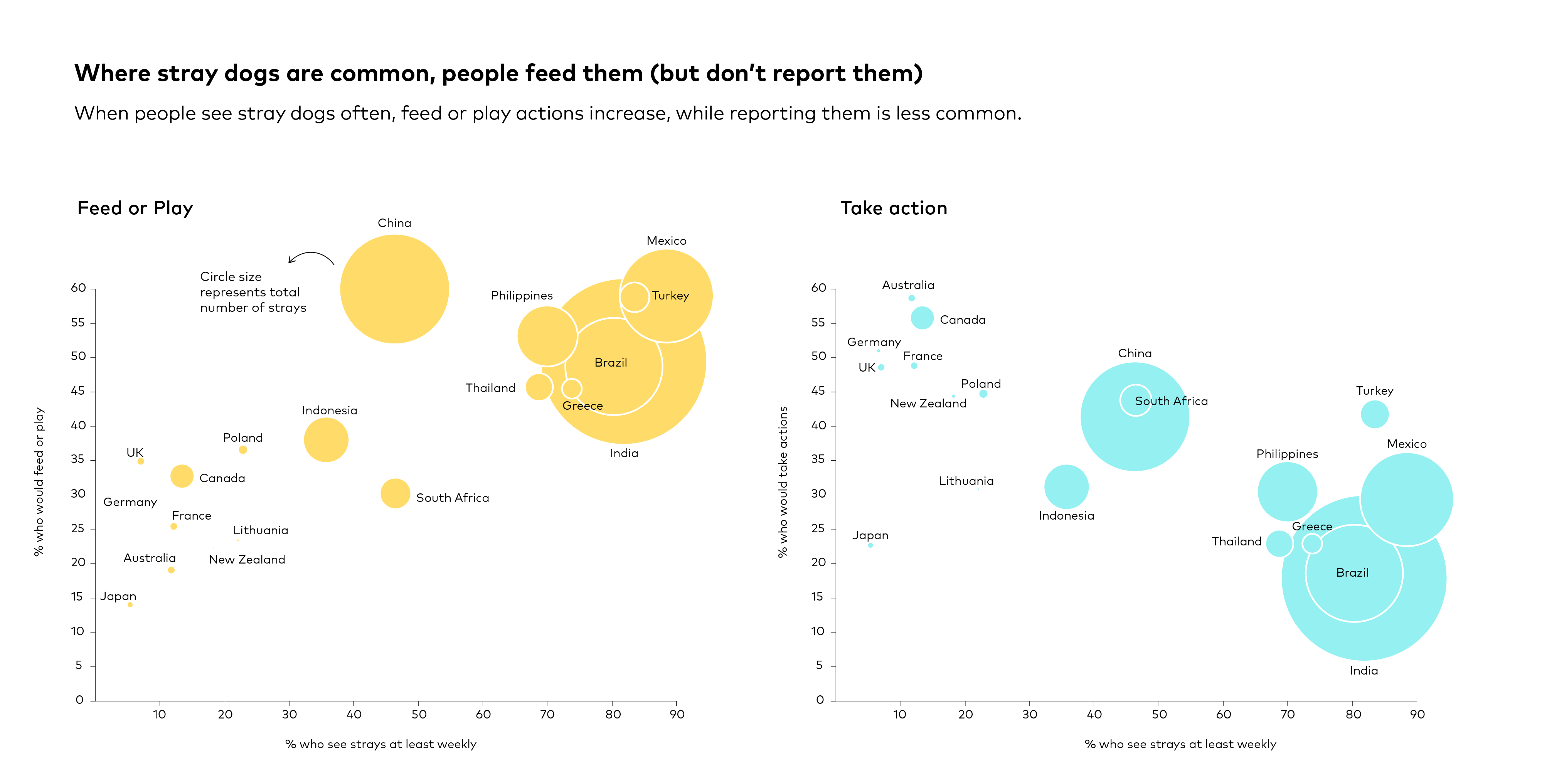

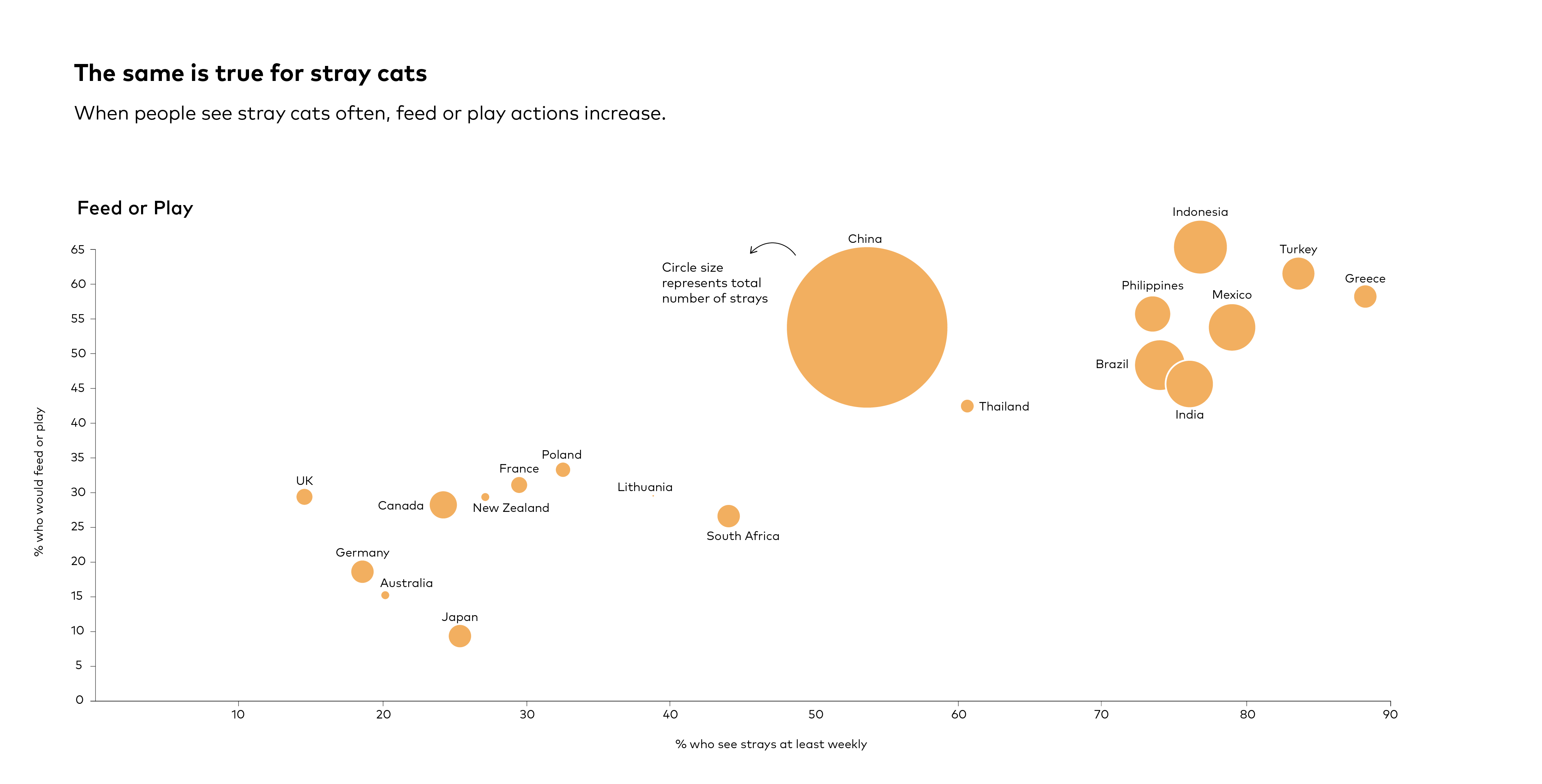

Digging deeper into the poll data reveals some telling insights. People living in countries where strays are relatively rare, like Australia, Canada or Germany, are more likely to take action to help them, mainly by trying to find the owner or reporting them to the authorities. On the other hand, people living in countries where strays are commonplace, like Mexico, Turkey or Greece, are more likely to be kind to them, principally by feeding them.

People tend to take the actions appropriate in their context, it seems. In rich countries, most cats and dogs are owned by someone and networks of shelters and other animal services are quite robust, so trying to find the owner or alerting local officials are both sensible things to do. But in the mostly lower-income countries where strays are a regular sight, nearby services to help animals are often overstrained, unreliable, or non-existent, and going looking for the owner is a futile endeavour. So people take matters into their own hands by feeding the street cats outside their window.

Charts 4 and 5: Where strays are common, people feed them (but don’t report them)

Varying levels of pet ownership between countries may also help explain the international differences. Intriguingly, the Mars Petcare survey provides some evidence that current pet owners treat stray animals differently than those who have never owned a pet. In Greece, India, and Indonesia, for example, never pet owners are about twice as likely to do nothing for a stray dog than those who currently own a cat or dog. This makes sense: having a pet arguably increases your empathy for animals, and animal lovers are surely more likely to become pet owners in the first place.

There’s an important caveat to all this: respondents were surveyed on what they would do if they saw a stray, not what they have done in the past. Some, undoubtedly, will have lied – as in every survey. And yet, even if many are only parroting the socially acceptable answer, the large differences in responses across countries show that what is deemed acceptable behaviour towards strays also varies greatly across the world.

So what should you do if you see a stray dog? Advice will differ by country but here in the UK the RSPCA, an animal charity, advises that you:

1. Check to see if the dog is wearing a collar with the owner’s contact details

2. Stay clear of an aggressive dog and contact the local dog warden

3. Report the stray dog to the local dog warden service

4. Contact the local vet to scan for a microchip (all dogs in the UK should be microchipped by law)

5. Contact local animal rescue centres and report the found dog

6. Report the found dog on an animal search website such as Animal Search UK

7. Use social media to spread the word

Stray animals are easy to ignore. But the Mars Petcare survey data reveals the staggering scale of the issue. If we want a world without dogs and cats on the streets, we can’t keep turning a blind eye to them. While the situation in each country is different, the solutions are broadly the same: sterilisation and neutering programmes, more reliable services for animals, and many more people stepping forward to adopt shelter pets. Reporting street dogs and cats, where systems exist to do so, is the first, crucial, step towards finding them a new home. If I ever do see that scruffy, collarless hound wandering around my neighbourhood, I’ll know not to walk past it.

About the data

Figures are based on an infogr8 analysis of a survey conducted on behalf of Mars Petcare from August 2022 to April 2023. This analysis includes data from 27,936 respondents across 19 countries (excluding the US). Percentages are weighted by the demographic characteristics of respondents to be nationally representative. The full survey data can be accessed using the State of Pet Homelessness dashboard, built by infogr8.