Insight

Data’s role in the face of economic uncertainty

Insight

Data’s role in the face of economic uncertainty

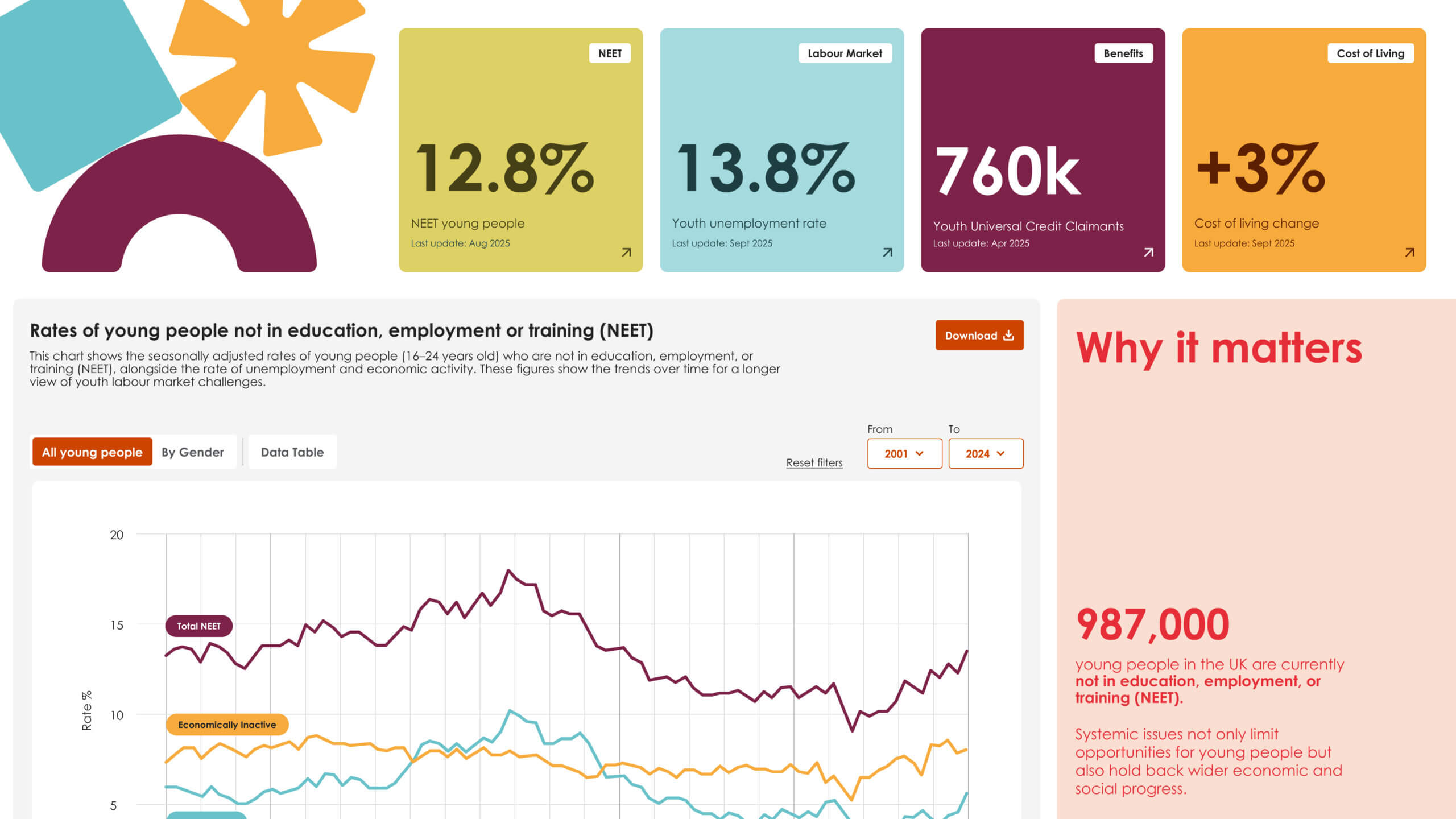

Composition of data dashboard

It is no surprise that anti-immigration sentiment tends to rise during times of economic uncertainty and downturns. History provides stark reminders: 1930s Germany, the 1970s oil crisis era in the US, and more recently, the European debt crisis that fuelled far-right movements across southern Europe. In each case, worsening job prospects and declining wages prompted people to look outward for scapegoats, rather than inward at structural issues.

When people feel their livelihoods are under threat, blame often falls on external forces – immigration, globalisation, or institutions. This tendency becomes especially potent when amplified by waves of populism: big claims, simple “solutions,” and little appetite for critical thinking.

But here’s the thing: anti-immigration sentiment is nothing new. What feels different now is its sharpness and omnipresence, supercharged by digital media ecosystems and political opportunism. In the UK, attention is repeatedly diverted toward symbolic distractions. ‘Small boats’, ‘asylum hotels’, headline-grabbing “crises”, while the real challenge lies ahead: economic opportunity.

A critical moment for the UK workforce

Rachel Reeves’ announcement of the Youth Guarantee could prove momentous. An estimated 948,000 young people aged 16–24 in the UK are currently not in education, employment, or training (NEET). That is nearly one in seven young people, approaching the highest level in over a decade.

This is not just a social issue; it is an economic time bomb. A generation locked out of education and work erodes future productivity, limits tax revenues, and fuels resentment that populists are all too willing to exploit. The UK’s long-term competitiveness depends on tackling this head-on.

When societies expand economic mobility and opportunity, everything else, the noise of scapegoating and culture wars begins to fade into the background.

Data’s role today

The rational, evidence-informed approach has always struggled against the populist shorthand. In 2016, detailed economic analyses of the EU’s benefits to the UK were no match for the bold, misleading simplicity of the Brexit campaign bus slogan.

It is not enough anymore to publish spreadsheets, release reports, or create intricate infographics that require minutes of attention. In a world shaped by ChatGPT, TikTok, and newsfeeds, people expect fast answers, bold figures, and clarity in seconds.

That doesn’t mean evidence has lost value. It means evidence must adapt. Data and narrative have to coexist. People need the quick headline and the ability to dive deeper if they choose. Trust is built when information is both accessible at a glance and defensible under scrutiny.

What can we do?

At infogr8, our work with Youth Futures Foundation provides a useful case study. Their challenge was the same one many institutions face: how to make complex youth employment data usable and trustworthy. Our solution was to create a single source of truth:

- Simple, human-centred UX that foregrounds headline statistics while offering intuitive routes to explore more.

- Trusted pipelines that ingest data directly from official sources like ONS and government APIs.

- Shareable insights that work across platforms, from dashboards to media-friendly snapshots.

This layered approach means users get what they need quickly and can validate it easily if challenged.

Competing in the attention economy of 2025

As populist narratives grow louder, the role of data is not to retreat but to evolve. Evidence will only win trust if it can:

- Compete for attention – through clarity, boldness, and relevance.

- Provide depth on demand – offering pathways beyond the headline for those who want to dig deeper.

- Anchor debate in truth – pulling from trusted, verifiable sources that withstand scrutiny.

Data’s role has never been more critical. The question is no longer just what evidence we have, but how we deliver it. If we want to counter noise with clarity and misinformation with trust, we must design data experiences that meet people where they are fast, simple, and credible.